How do you get started on a project that’s unlike anything your organization has done before? What about a project that is highly collaborative, involving multiple departments or institutions that haven’t yet have worked together on a project of this scope or type?

Let me walk you through the first steps of initiating a project like this, using a specific example of a digital collections project in an academic institution. This example is based on a job talk I gave a few years ago that led to becoming project manager for a grant funded digital collections collaboration project1, refined with additional insights I’ve gained by going through this process a few more times in the intervening years.

Beyond digital collections and higher ed, this process is applicable for other types of projects that rely on forging new collaborations across siloed departments or between independent organizations. Less collaborative projects that rest in a single established group may already have some procedures or templates defined which will make the initiation process more streamlined, but the same explorations of shared language, defining the project, and the people involved will serve you well.

Example College Audio Omnibus Project

Let’s say that somebody at Example College has noticed that many different departments and institutions have audio recordings in their possession.

For example, the libraries have books on tape, commercial music CDs, and oral histories. The art museum has recordings of visiting artist and curator talks, a collection of experimental audio art, and audio recordings of past site-specific multimedia exhibitions. In the college archives, there are decades of commencement speeches, faculty research recordings, and so on.

In some of these departments, the recordings are in regular use and accessible to students, scholars, or even the general public. In others, they are meticulously cataloged and preserved, but not accessible without insider knowledge. In yet others, the recordings are there and vaguely understood, but not organized or cataloged. Based on this, it’s likely that there are even more in places that we don’t yet know!

So it’s been decided that it would be great to get a better understanding of Example College’s audio collections as a whole, and find ways to unify the materials and make them more accessible and useful to the Example College community. A budget is set, several months allocated for the project, and you’ve been hired or assigned as the project manager. Now we have a project, and it’s time to initiate it!

What does it mean to initiate a project?

Once a project has been decided in the broad, general terms above (which itself might take a few years of wrangling in academia) we need two things:

- A detailed DEFINITION of the project that is understood and agreed on by all the participants and the people in charge

- An understanding of the STAKEHOLDERS–a list of everyone who is involved, contributing, and/or affected by the project

It’s your job as project manager to organize and deliver both of these things, and get ready to move on to the next stage.

The initiation stage is extremely important, and needs to be given the time and resources necessary for success. If you rush it, you’re going to end up either re-doing some of these steps later on in the project, or you’re going to come out the other side with an outcome that’s not what all of you (or any of you) actually want or need.

At the same time, we will be building the framework for the rest of the project.

Shared Language

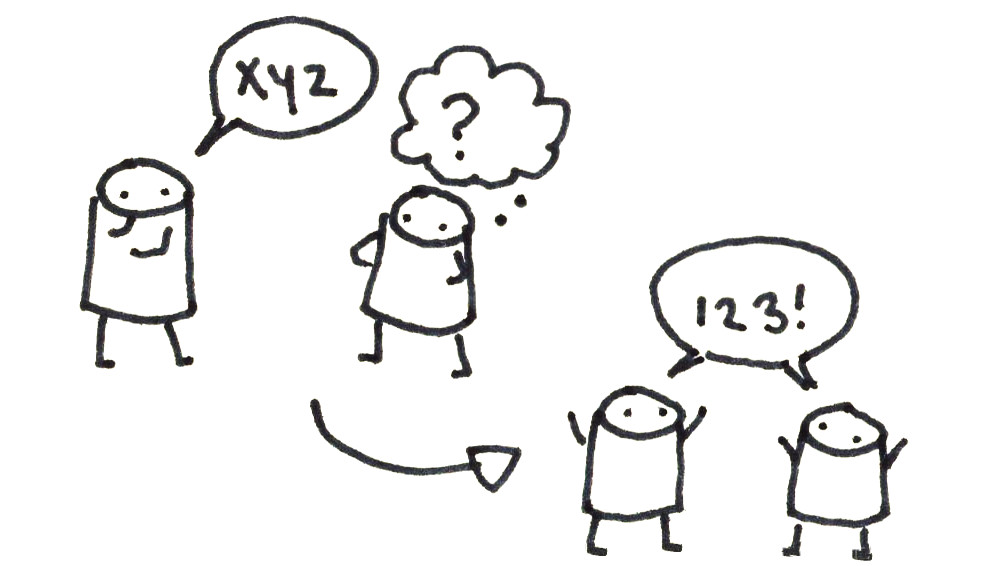

Initiation is the time to develop our SHARED LANGUAGE for the project.

When we’re doing something as intensely collaborative as this, we need to be aware that words don’t always mean the same thing to different people!

In the case of our hypothetical Example College Audio Omnibus Project, I would bet that you already know that different departments and institutions mean different things when they say the words “archive” or “catalog” or “digital” or even “student,” right? Right.

So, the idea of shared language is crucial if we want to avoid getting six months down the road and finding out that the art museum thinks that we mean one thing, while the libraries think we mean something very different when we’re developing a tool for “cataloging!”

For you as project manager, especially if you’re coming in from outside, it’s also the time to learn what each of the collaborating partners mean when they talk about your audio recordings, so that you can be part of bridging those language and understanding gaps that will still inevitably crop up. It’s not on you to tell someone what “archive” means, but it is on you to let them know what their other colleague means when she says “archive” so that you’re all on the same page.

During initiation, we’ll also be figuring out how we will communicate within the project team and on an organizational level:

- What tools will we use to talk to each other? Will we be using endless reply-all email chains for eight months (please no)?

- How will we share project files and information? Do we have a shared storage drive? Shared project management software?

- How often will we meet in person or Zoom, and who should attend?

- Will we use pneumatic tubes or carrier pigeons?

Some of these methods will work better than others, but none of them will work if we’re not actually using them together. If one collaborating department is all-in on Slack, while another has staff who have never logged in, we’ll need to do some training and negotiation before deciding to use it for project communication. So we need to take this time right up front to figure out how we’ll stay in contact and move forward together over the rest of the project.

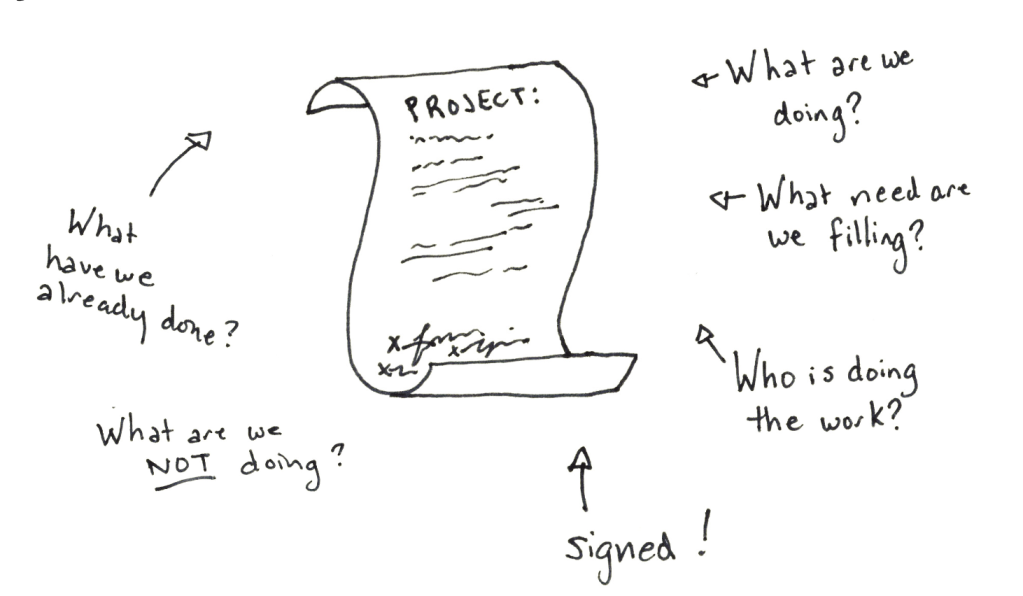

Defining the Project

The Project Definition is a detailed expression of what we are hoping to accomplish, what need or goal it satisfies, and how we will approach it. This is the time to get a lot more in depth than just “we’re going to do something with all that audio.”

Perhaps we’ll start with something like this to introduce the project:

We will complete a full review of all Example College departments and institutions, building an inventory tracking audio holdings by type, format, scale (number of recordings, data volume, etc), noting the state of cataloging, metadata, preservation, and accessibility for each collection. We will determine immediate, short term, and long term strategies for managing these audio resources and opening them to the Example College community. This will address the present gaps and inconsistencies of stewardship, discovery, and equitable access relating to audio resources held by Example College.

The project definition should also set out the big picture shape of budgets and deadlines. These will be developed in much greater detail in later steps, but we need a framework to get started. When the definition is developed into the formal project charter2, it will also include a description of what’s already been done, in previous projects or earlier discovery phases, and specify what this project isn’t going to do, what’s out of scope.

Given that this is a limited project in terms of time and resources, we might specify that we aren’t going to do any work related to creating new audio recordings, only work with ones that already exist or will be recorded in the normal course of operations by various departments.

Finally, the Definition is not complete until it is agreed to and signed off on by the project team and key stakeholders. Which brings us to…

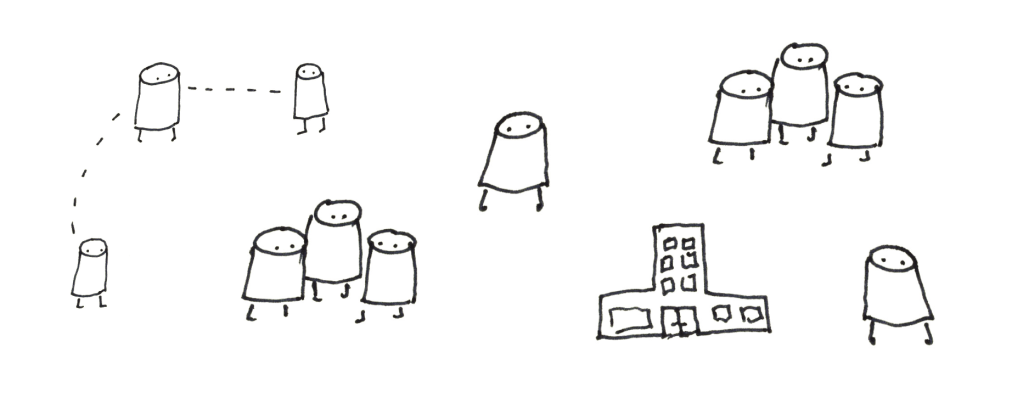

Stakeholders

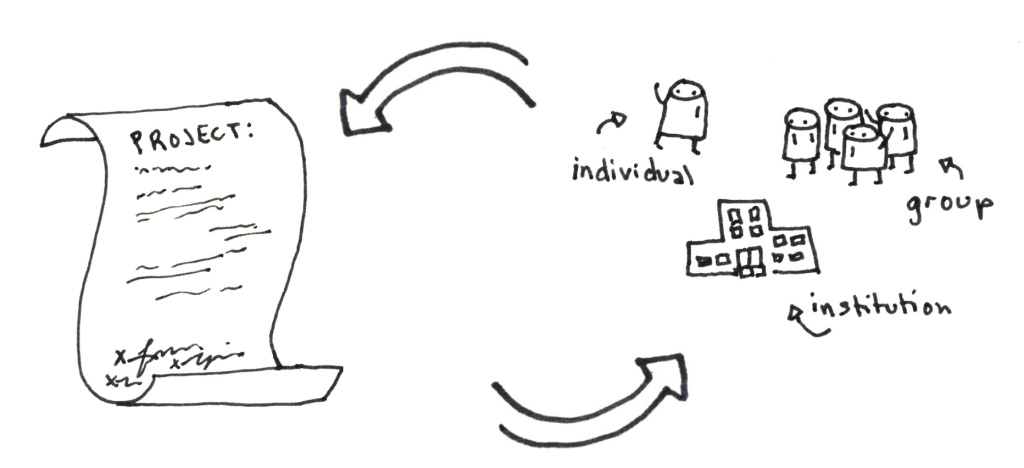

Stakeholders are people – individuals, groups, and institutions, who contribute to the project, plus anyone who will be affected by the project and its outcomes.

So, stakeholders for the Example College Audio Omnibus Project include the project team, the department managers, the sponsor–the person who authorized the project and is able to say yes to budget and other resource allocation needs–and any additional staff who will be pulled in to work on some aspect of the project.

It will also include:

- Staff and faculty who work in a department that creates or holds significant audio recordings

- Faculty who use recorded material in their classes, and their students

- Researchers who work with Example College audio materials–maybe affiliated with Example College, maybe not

- Peer colleges, museums, archives, or other institutions who are working on similar projects that might intersect

- People who will never actually listen to the recordings or use them personally but benefit from knowing the recordings exist and are being cared for

The full range of stakeholders can get extremely large and complex (ahem, last bullet point above), especially for a collaborative project. Each time we talk to a stakeholder, one of the things we’re hoping to learn from them is who else we need to add to our list. For example, when we’re interviewing educators in the art museum about their audio holdings, we hear that the fine art department has their own distinct stash of lecture recordings from visiting artists, and we really need to talk to them too. Think of your list of stakeholders as a living reference document, always growing and contracting as the project evolves, and a resource you should frequently consult to make sure you’re keeping all the needs and personalities in mind.

At the end of initiation, we want as complete a list as possible of *all* the stakeholders, and we want a detailed analysis of the ones who are key to the project. Key stakeholders will include:

- A few representatives from each of the partner departments

- Individuals who have shown particular interest or passion for the project

- People with expert knowledge that we will need to tap into throughout the work

This should be a shorter, more manageable list, enhanced with contact information, records of interaction with the project, and notes from the project team. Flag people who are especially excited about the project, and those who may see big changes in their jobs or research based on how our project works out.

We’ll also need to have an idea about who among the stakeholders are unhappy or resistant about this work, especially if they have the institutional power to throw up roadblocks or derail the project. Perhaps we need to clarify things with them so they understand better, perhaps we need to be prepared to change course to mollify them, perhaps we need to be ready to work around them, or perhaps they are resistant because they know something we don’t! It’s all important information and will shape how we move forward over the coming months.

Iteration

Working to uncover and engage with stakeholders will turn up exciting surprises. Remember how we found out about the fine art department from the art museum? Well, when we talk to the department admin there, we learn that the botanic garden has some amazing recordings of the sound of orchids growing–we’d never have thought of that! Then when we go talk to the botanic garden staff, it turns out that those recordings are on reel-to-reel tapes from the sixties, and haven’t been digitized.

This is a great example of how the process of seeking out and talking to stakeholders gives us information that has to feed back into the project definition. Should we work multi-format digitization into the scope of the project? I can tell you from experience that it’s a massive undertaking, but if our goal is to make materials widely available, maybe it’s central and we have to prioritize it. On the other hand, maybe we decide that digitizing is outside our present scope, but we will survey and inventory analog collections as well as digital audio, and let digitization be a project unto itself. If we decide that we will do something with digitization, that may suggest a whole new group of stakeholders, and when we talk to them, they will give us more information to feed back into the project definition. So you see that the entire process of initiating a project can be imagined as a spiral rotating between the definition and the stakeholders, with the project manager and the project team spinning the wheel and recording the results.

Almost Ready

This could go on forever, but at a certain point the project manager and their team need to decide that we have enough, and we’ll draft the final project charter and get it signed by the project team, the sponsors, and the other key stakeholders.

Your charter will include all the things I talked about before, describing how we’ll know that we’re done, and articulating our project values in line with the larger institutional commitments of Example College. We’ll define things like transparency, accessibility, and equity in the context of this project. We’ll also lay out the structures of accountability–how we’ll be held to the scope of the project and to the values that we’ve defined within it.

Doing this work thoroughly and well will give you the foundation you’ll need to carry out the work of the project and create successful outcomes.

Aren’t you excited to get started?

Notes

- https://libraries.smith.edu/about/projects-initiatives/stronger-together

- There are lots of templates and standards out there for project charters. Ask around in your institution to see if there’s an already accepted format, and if so adapt that for your use. If not, look for examples in your industry or discipline.

Leave a comment